Preparing for Delft High Performance Computing (DHPC)

What’s it all about?

The TU Delft is currently setting up its High Performance Computing facility (DHPC).

What will this mean for researchers at the TU Delft? How does a cluster of computers actually work? How do you go about taking advantage of such a facility? What do I need to know about parallel computing, before I can support TU Delft researchers using DHPC?

DHPC is basically a large number of computers, connected together in a clever way. So, in order to answer some of my questions, I decided to prototype my own computing facility, using Raspberry Pi computers. The DLPC (Delft LOW performance cluster) was born.

I spent several happy hours following the instructions in this excellent book: “Raspberry Pi Supercomputing and Scientific Programming: MPI4PY, NumPy, and SciPy for Enthusiasts”, by Ashwin Pajankar, ISBN 978-1-4842-2877-7.

Without too much trouble I managed to cobble together a computer cluster from 8 Raspberry Pi 3 model B, a fast ethernet desktop switch, a pile of cables and power supplies, and a role of hook-and-loop fastener. The only aspect I managed to waste a lot of time on was the network. This was due to a faulty cable, my typing mistakes and me not really knowing enough about computer networks. Reading the instructions again and again, switching cables and checking the network interface configuration files many, many times, finally paid off.

I was left wondering if that little plastic clip you are afraid will break off, could be the most robust part of a computer network

Since there is a lot of focus on learning Python at the TU Delft, I decided to concentrate on mpi4py. This is an implementation of the Message Passing Interface standard for the Python language. Basically, it enables my Python scripts to run in parallel on a cluster, spreading the workload over different processors and giving me results faster … if I use it correctly.

When you know it should work

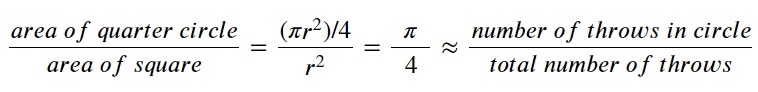

A classic example of when parallel computing should speed up a calculation is throwing darts to calculate π. If you have a square dart board with the largest quarter circle possible painted on it, you can estimate the value of π from the number of throws landing inside and outside the circle. One line of maths for those who are interested:

In principle, the more throws, the more accurate your estimation:

As you can see, with 1000 dart throws, the value of π is already approaching the true value (≈3.14159). I decided to stick with 1,000,000 dart throws for the next part.

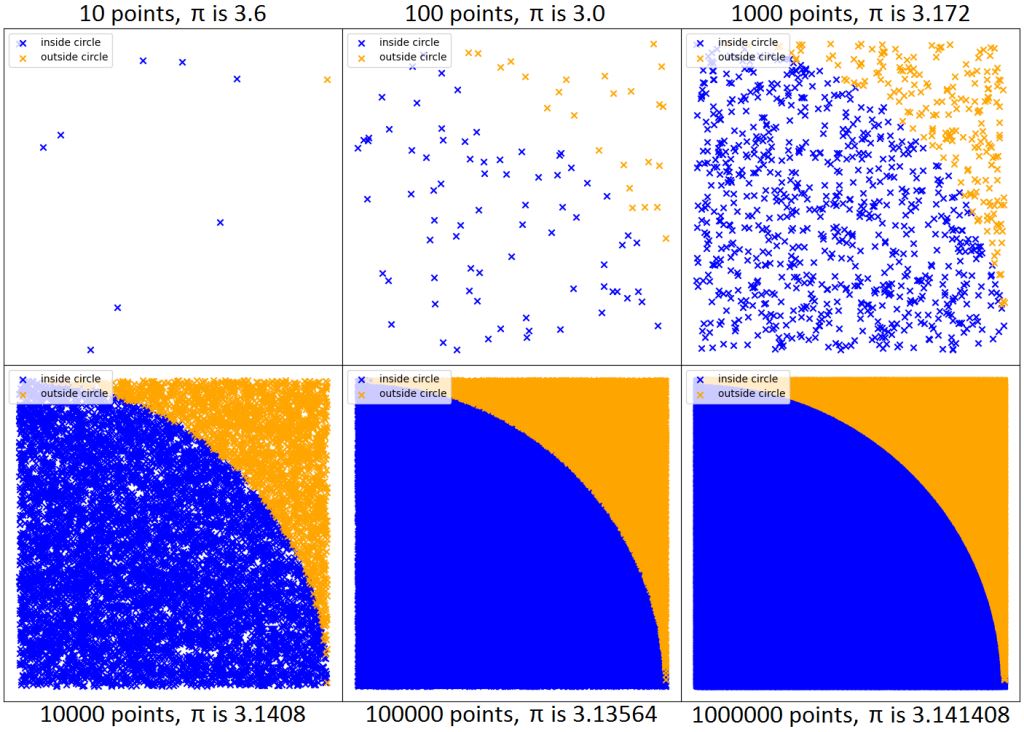

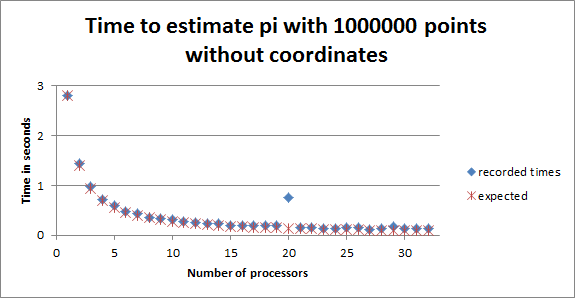

The DLPC has 8 Raspberry Pi computers, each with 4 processors. This means that I have 32 processors, or ranks, to play with. I set up calculations to distribute the 1,000,000 dart points over 1, 2, 3, … 32 processors. I was expecting that if I used 2 processors it would take half the time; and with 10 processors a tenth of the time (and with N processors, (time for 1 processor)/N). This is what I got:

As you can see, I wasn’t getting the performance speed-up I was expecting (1/N). I removed a load of print statements that I used for debugging, but that didn’t help much.

I started to discuss this with a nearby scientist and tried to convince him that this was due to unavoidable communication between the processors. He didn’t believe a word! Not being able to convince him I was right, I investigated further and eventually discovered what the problem was.

I really wanted to show you how increasing the number of dart throws increases the accuracy of the estimate for π, so I wrote back all the dart point positions (x- and y-coordinates) and the inside/outside statuses from the worker processors to the central manager processor. This is how I could make the dart board figures above. It turns out that this communication was killing my performance. A classic beginner’s mistake. Once I only wrote back the number of dart points inside the quarter circle from each processor back to central manager processor, things got a lot better:

This was great, except for that strange point at 20 processors. Not sure what happened. Could have been that I accidently pulled on the network cable, or that a Raspberry Pi got too warm, or that I got impatient and took a look at what was going on, which slowed everything down, or a bug really did crawl into the DLPC.

Now I was left with the question: when shouldn’t you invest your time in making something work in parallel?

When you know it shouldn’t work

Parallel computing doesn’t work well for inherently sequential problems, but what does that mean?

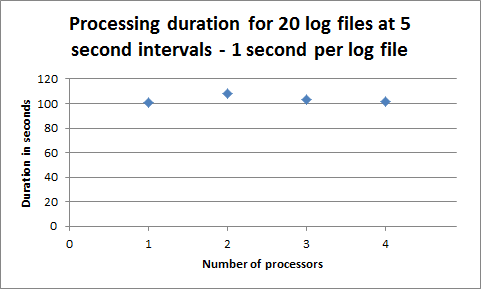

I decided to simulate an experiment that takes measurements at regular intervals and writes them to log files. These log files then have to be analysed. The fact that the log files are produced sequentially makes it impossible to process them all in parallel, in real time, hence this is an inherently sequential problem.

My simulation consists of measuring the temperature of the manager Raspberry Pi (using the vcgencmd command), writing the time and the temperature to a log file and then waiting for 5 seconds before taking the next measurement.

The analysis is independent of the measurements and consists of reading a log file as soon as possible, extracting the date, time and temperature and then waiting for 1 second (to simulate the analysis). I did this ‘analysis’ for 20 log files in total.

It takes 100 seconds to take 20 measurements, so a total time of 101 seconds is the minimum time needed. As expected, increasing the number of processors doesn’t speed up the total time. You just have to wait for the experiment to produce the numbers, before you can analyse them.

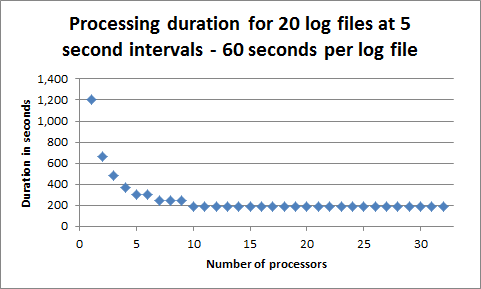

My final step was to find the point where parallel processing would break down and adding more processors wouldn’t help. For this I kept the ‘experimental temperature logging’ the same (5 seconds between each measurement for 20 measurements), but changed the analysis time from 1 to 60 seconds.

The time taken to measure the temperature is the same as before (100 seconds). The difference is that it takes 60 seconds to analyse the measurement, so sometimes you have to wait for a processor to become available before you can analyse the next measurement.

Here you can see that 5 processors already give a good performance improvement and more than 10 is a waste of processors. The optimal number of processors depends very much on the problem you’re trying to solve.

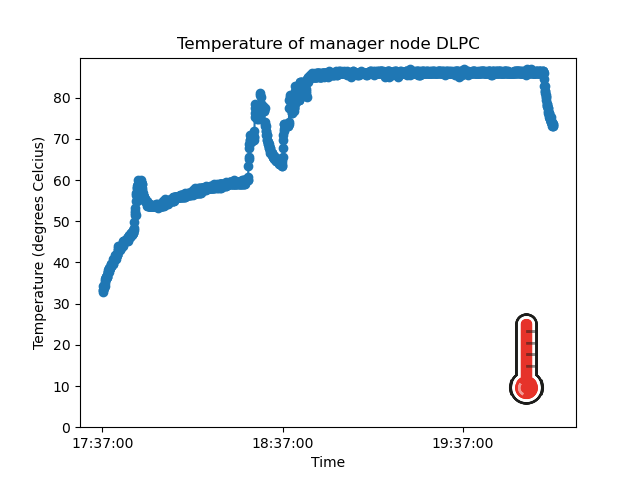

For those of you who are curious, here’s what happened to the temperature of the DLPC during these experiments:

You can clearly see the heating up at different rates, depending on the processing and communication loads, and the cooling down periods, when the DLPC was waiting for its next task.

Lessons Learned

Communication is hard, time consuming and error prone, whether it’s between:

- humans – trying to write a blog that is informative for both researchers and research support staff

- humans and computers – learning a new kind of software programming

- computers – getting processors to share just enough data at the right moment

Managing hardware and networks is hard, time consuming and error prone. Getting the right information and software packages on the 8 Raspberry Pi-s and keeping them up-to-date is something I could only achieve through automation. I now have even more respect for my colleagues at IT.

Running in parallel can dramatically improve performance, but you have to choose your problem wisely and be careful about your implementation.

You don’t have to run in parallel on a cluster. You can run everything on one processor, it just might take longer.

Resources and Acknowledgements

If you want to build your own Raspberry Pi cluster, then this book has very clear instructions: “Raspberry Pi Supercomputing and Scientific Programming: MPI4PY, NumPy, and SciPy for Enthusiasts”, by Ashwin Pajankar, ISBN 978-1-4842-2877-7.

If you’re interested in MPI, but not necessarily in Python, then this TU Delft course is excellent. I’m hoping there will be so much demand that Kees Vuik and Kees Lemmens will let me be a helper next time, so please sign up!

This PRACE training Parallel and GPU Programming in Python takes a broader look at speeding up your Python code. Well worth checking their website for future events.

You can find my scripts here.

Laurens Siebbeles is gratefully acknowledged for relentless discussions.

Mark Schenk is gratefully acknowledged for paying for this adventure and sharing my enthusiasm.

Raspberry image by PublicDomainPictures on Pixabay.

This blog expresses the views of the author, Susan Branchett.

This article is published under a CC-BY-4.0 international license.